The raw silks of Thailand

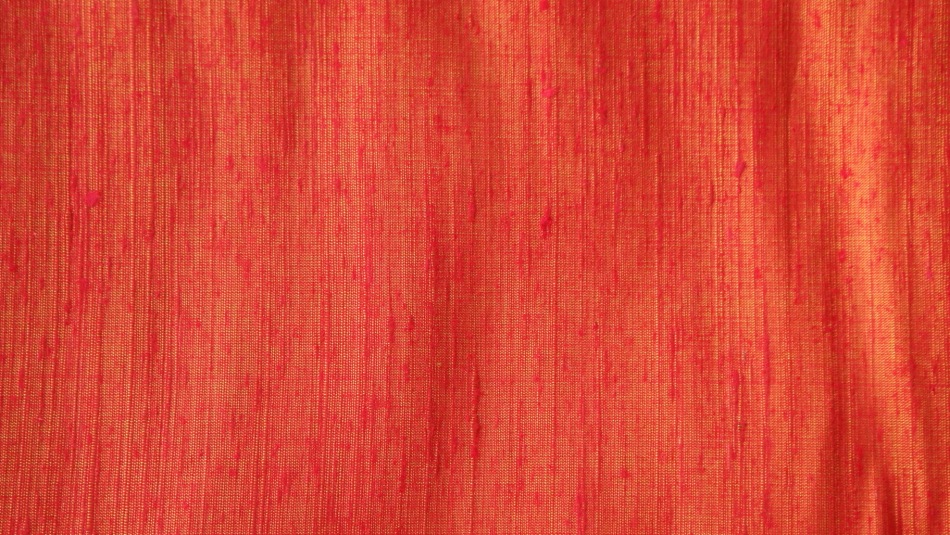

“Raw silk” is silk woven from “the first spin”. Silk cocoons are dumped in boiling water, whereupon the glue holding the string together dissolves and the pot becomes full of mingled, endless thread. One grabs it anywhere and begins to “spin” — rolling it between his fingers while pulling what emerges from one’s hand onto the spinning wheel — trying to get as thin a thread as one can — i.e. one made up of as few fibers as possible. The first spin is invariably a little rough and bumpy, thicker in places and thinner in others as it is knotted, mottled, and various bits of flotsam adhere to it. Later re-spinnings eventually work out the kinks, producing very thin, uniform thread; which is used to weave fine cloth like satin; but the first-spin — in places as thin as the real McCoy, elsewhere as thick as hemp string — can also be used to weave cloth. This is known as Raw Silk. It produces the texture you see above: rough to the touch, uneven, with pronounced individual threads, a bit like the bark of a tree.

Shot silk is silk woven with contrasting warp and weft colors, resulting in a cloth which appears to gleam and shift colors as you turn it before your eyes. These four examples are, top to bottom, red and black, orange and blue, orange and red, and blue and red. Note how they gleam around the fold: this effect — the unique property of shot silk — is especially strong when the cloth is worn as clothing and the wearer moves: she appears to shimmer.

Shot silk is especially effective in satin silk, a type of weave which uses the thinnest, finest thread, and leaves long stretches of individual threads unwoven (“floating” along the surface); this makes the cloth easy to damage, but gives it smooth surface (“smooth as silk”) and brilliant sheen: it seems like the cloth has been woven from pure sunlight reflected on water.

Weaving raw silk as shot silk, on the other hand (as these examples all are) produces a different — and extraordinary — effect: the seamless shifting of colors between the colors of the warp and the color of the weft — the shimmering of light reflected on water — is interrupted by the rough feel created by the the uneven thread. As you bring your face closer to the cloth, the liquid smoothness resolves into dry roughness: it is a lot like a tender kiss suddenly turning into a bite.

The colors of which these four are made up — red, purple, orange — are the basic colors of the Thai language. Purple (Si Muang) and orange (Si Seet) are the two most popular colors in Thailand, seen everywhere: in homes, in clothing, in company colors, on official logos. Not for Thais the dullness of less is more: nature would not allow it; among the intense colors of South East Asia’s nature, “less” really does look like less.

Ten years ago, Kad Luang (“The Old Market”) in Chiang Mai had at least a dozen shops selling silk, both raw and satin, lined along the walls with a fantastic range of colors, starting with white on the left, going through various shades of white (“Monsoon clouds”, “Moon in August”, “Tiger tooth”) to shades of grey to shades of beige to shades of cream, and so on and so on, to umpteen shades of green, umpteen shades of red, umpteen shades of purple, ending, at last, on the far right, at the far end of the store, in several shades of black.

Today only three shops remain and they have, between them, at most 20 meters of linear shelf-space of colored silk; you’d be lucky to find four reds to choose from. The shop owners, there day in and night these twelve years, have not noticed the change, it has been so gradual. But the truth is that silk retail is dying.

Why?

It isn’t the prices: it costs in Thai Baht what it cost ten years ago, a modest 25% climb in dollar terms (between $12 and $18 per meter today). Rather the problem is on the demand side: the government rule that all government employees are required to wear Thai silk on Fridays has been rescinded; marketers have convinced the feeble-minded that denim and spandex are more chic; but, mainly, tailors have gone and closed.

Why do tailors close?

Who knows?

Twenty years ago I tried, in vain, to convince an otherwise intelligent and enterprising Polish man, that clothes made to measure will cost him less and fit him better than an off-the-shelf Ferragamo, but he refused to hear good sense. Perhaps, like many people, he felt helpless in his inability to visualize what he would like for himself. When asked by the master craftsman “Would sir like a double-breasted jacket or a single-breasted one?” most people reply “Oh, I don’t mind” meaning not that they do not care, but that they don’t have a clue what they want. (An apt metaphor for the whole of their life). The store with ready made clothes offers three choices — which has the virtue of being easy to choose from, even if none is especially good; but the tailor offers endless opportunities; which is, despite Hollywood propaganda to the contrary, not what people want. Don’t ask me what I want. I don’t know what I want. I want everything. I want nothing.

Tracking down my old tailor last month, after three years’ absence, I discovered he had moved to the suburbs and his waiting time is now not three days but — three months. This is not a measure of his success but a measure of the profession’s failure: no one else sews anymore; he is the last tailor shop left in town (not counting the fake, tourist “suit and two shirts” shops which do not actually know how to sew, just how to sell). His prices aren’t up, just like the flat prices of silk, but his waiting times are. His customers are old timers who had learned in better times how to have things tailored (i.e. how to visualize what they want and then instruct it) but can’t afford a higher price: they will rather wait three months than pay more. The younger generation have the money, just no clue what they could tailor, or even that they could.

And yardage — yardage will only sell if you can sew it. If you don’t know what to do with it, you’re not going to buy it, are you?

This is how the demise of one profession (tailoring) leads to the demise of another (weaving). But, hey, no loss without compensation: you can buy 80-dollar T-shirts from LuLu now, mostly in shades of grey, in machine-spun spandex.

I went out and bought four meters of every length of shot raw silk I liked, figuring that, at this rate, in two years’ time when I return again, there won’t be any left.

How to (properly) read a portrait

Although Gulbenkian will tell you that

the model’s expression suggests his intellect and wisdom. The artist manages to capture an apparently informal moment and turns the subject into a living, imposing presence.

the truth is the precise opposite and the painting suggests something completely different: Monsieur Louis Duval d’Epinoy, the king’s secretary, unnamed by any document of any importance other than a brief mention that His Majesty Himself had once gracious agreed to be a witness at his daughter’s wedding, was simply a great guy to be around. Look at that pixish sense of humor, the ebullient delight in life, and the complete and utter lack of self-importance: everyone simply loved to be in his company, His Majesty included. (Wouldn’t you?) Monsieur d’Epinoy and his inconsequence (i.e. his lack of interest in social climbing) made it easy to do so. His easy going nature made him the success he was: his success was founded on not seeking one.

Monsieur d’Epinoy was also a bit of a pot-head (he’s fingering in his snuff box with an expression suggesting he’d already had a hit — and — look at his enlarged, reddish nostril: he clearly was want to have many throughout the day).

And, why not? When everyone loves ya, life’s a breeze, is it not? Why not kick back and enjoy it.

We do agree with the rest of the Gulbenkian comment, though:

In its age, this work was considered to be an absolute triumph of pastel painting and the finest portrait that Maurice-Quentin de La Tour had produced.

My first soumak, or, a historically-informed performance ruggery

It is, no doubt, a measure of my superior negotiating skills (not!) that the price of this carpet went up as we negotiated. I tell myself it was a good learning experience and I will be able to do better next time, but I am kidding myself: the truth is that no one ever wins against a carpet seller.

Actually, it is not a carpet (a knot-weave) but a soumak — a kind of flat-weave, similar to kilim, but different from it in that it sports an invisible (“internal”) structural weft. This useful, well illustrated page pretends to show you how to weave a soumak, but doesn’t: what they do there is a kilim; this technique is the one used in making European tapestries. A soumak will in addition have some fixed threads running left to right (“weft”). These threads support the structure of the cloth and make it stronger. They are hidden under the color threads (which make the pattern) but if you stick your finger in the fabric and poke about, you can just make them out under the pattern.

This soumak was woven perhaps 15 years ago in Tabriz by Azeri weavers. It was woven out of old threads pulled out from old cicims, which is why it has the intense colors of historical carpets — few modern carpets look this “authentic” — it is, in other words, “a performance on original instruments”. A good deal about soumaks is explained here (along with some historical examples). My favorite page on that website is the page about the Luristan bronzes (mother goddess, totemic animal finials et al.) — which only illustrates how sophisticated was the weaver of my new rug — he knew to play with all the totemic animals and all the rest: it is a “historically informed performance”. Like a mamluk, it pleases in its ability to surprise: seemingly symmetrical, when you look closer at it — it isn’t.

Actually, Luristan bronzes are pretty cool as well as mysterious (we don’t know who made them or what they meant). Check out this for some examples, and this for some discussion.

Victoria and Albert: The Triumph of Death

isn’t: it is the triumph of life, symbolized here by The Fates. In the end, of course, death does win, but death only exists where there is life to begin with: the image of the three sisters standing atop overturned Chastity make the meaning plain: for life to go on, Chastity must be overturned. Ladies, think about it.

This is a subversive joke, of course; so the makers felt compelled to pair it with the Triumph of Eternity, an ugly thing showing St Jerome and St Augustine (say the credits, though I think it’s actually Saint Sylvester the Pope) riding in a chariot over the overturned Fates. That pleased the powers that were — but we don’t have to look at it.

Recent Comments