Quick and dirty rules of thumb for more efficient cultural life

Cultured life entails many risks. The chief risk is – waste of time. The amount of culture available for consumption compared to one’s limited days on earth is practically limitless and the vast majority of it is garbage.

Because time lost is never found, every hour wasted is an irreparable loss. (And sometimes it is worse: reading an indifferent book is only a waste of time while one is reading it; but reading a bad book about which one subsequently thinks with revulsion or disgust ruins more than the time spent reading it).

How to avoid expending one’s precious, dwindling resource — time — on stuff that does not deserve it?

This is tricky business because so many works attempt to deceive us as to their quality: they pretend to be original or high brow or ambitious. (They put on names such as “symphony” or “ode” or “novel”; they adopt the style of masters; quote or make references; pretend to be a meaningful response to great works; etc. etc. etc).

One must develop quick guidelines – “rules of thumb” – to allow one to detect-and-neutralize garbage before the damage is done. Some such rules are extremely efficient: e.g. some require that you do not go near certain category of works at all (e.g. biopic, music fusion); others can deliver a verdict within minutes (last night I aborted a movie after 4 minutes).

As new forms of deception are constantly invented, new defensive rules of thumb must be constantly developed and adopted. Here are two new rules I adopted this week:

1. Avoid books with clever titles (e.g. How to Live: Or A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer or How To Be A Great Artist On The Example Of Thomas Mann). A clever title betrays an effort expended on the cover and great books don’t need catchy covers. (Vide “Doktor Faustus”).

2. Avoid concept books (Jarosław Mikołajewski, Rzymska Komedia, attempts to be a series of essays about Rome using the Divine Comedy as a guide: this makes no sense, I can’t believe I let myself be so easily duped).

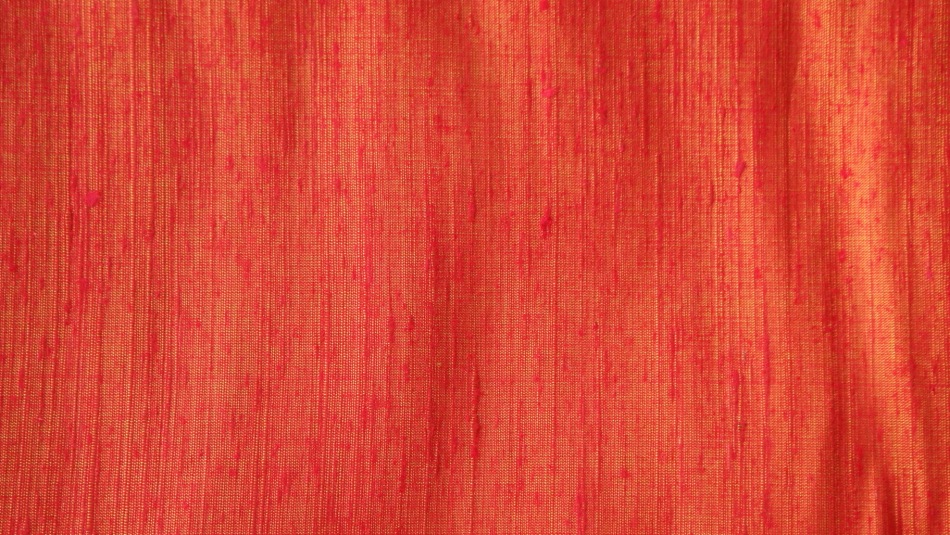

The raw silks of Thailand

“Raw silk” is silk woven from “the first spin”. Silk cocoons are dumped in boiling water, whereupon the glue holding the string together dissolves and the pot becomes full of mingled, endless thread. One grabs it anywhere and begins to “spin” — rolling it between his fingers while pulling what emerges from one’s hand onto the spinning wheel — trying to get as thin a thread as one can — i.e. one made up of as few fibers as possible. The first spin is invariably a little rough and bumpy, thicker in places and thinner in others as it is knotted, mottled, and various bits of flotsam adhere to it. Later re-spinnings eventually work out the kinks, producing very thin, uniform thread; which is used to weave fine cloth like satin; but the first-spin — in places as thin as the real McCoy, elsewhere as thick as hemp string — can also be used to weave cloth. This is known as Raw Silk. It produces the texture you see above: rough to the touch, uneven, with pronounced individual threads, a bit like the bark of a tree.

Shot silk is silk woven with contrasting warp and weft colors, resulting in a cloth which appears to gleam and shift colors as you turn it before your eyes. These four examples are, top to bottom, red and black, orange and blue, orange and red, and blue and red. Note how they gleam around the fold: this effect — the unique property of shot silk — is especially strong when the cloth is worn as clothing and the wearer moves: she appears to shimmer.

Shot silk is especially effective in satin silk, a type of weave which uses the thinnest, finest thread, and leaves long stretches of individual threads unwoven (“floating” along the surface); this makes the cloth easy to damage, but gives it smooth surface (“smooth as silk”) and brilliant sheen: it seems like the cloth has been woven from pure sunlight reflected on water.

Weaving raw silk as shot silk, on the other hand (as these examples all are) produces a different — and extraordinary — effect: the seamless shifting of colors between the colors of the warp and the color of the weft — the shimmering of light reflected on water — is interrupted by the rough feel created by the the uneven thread. As you bring your face closer to the cloth, the liquid smoothness resolves into dry roughness: it is a lot like a tender kiss suddenly turning into a bite.

The colors of which these four are made up — red, purple, orange — are the basic colors of the Thai language. Purple (Si Muang) and orange (Si Seet) are the two most popular colors in Thailand, seen everywhere: in homes, in clothing, in company colors, on official logos. Not for Thais the dullness of less is more: nature would not allow it; among the intense colors of South East Asia’s nature, “less” really does look like less.

Ten years ago, Kad Luang (“The Old Market”) in Chiang Mai had at least a dozen shops selling silk, both raw and satin, lined along the walls with a fantastic range of colors, starting with white on the left, going through various shades of white (“Monsoon clouds”, “Moon in August”, “Tiger tooth”) to shades of grey to shades of beige to shades of cream, and so on and so on, to umpteen shades of green, umpteen shades of red, umpteen shades of purple, ending, at last, on the far right, at the far end of the store, in several shades of black.

Today only three shops remain and they have, between them, at most 20 meters of linear shelf-space of colored silk; you’d be lucky to find four reds to choose from. The shop owners, there day in and night these twelve years, have not noticed the change, it has been so gradual. But the truth is that silk retail is dying.

Why?

It isn’t the prices: it costs in Thai Baht what it cost ten years ago, a modest 25% climb in dollar terms (between $12 and $18 per meter today). Rather the problem is on the demand side: the government rule that all government employees are required to wear Thai silk on Fridays has been rescinded; marketers have convinced the feeble-minded that denim and spandex are more chic; but, mainly, tailors have gone and closed.

Why do tailors close?

Who knows?

Twenty years ago I tried, in vain, to convince an otherwise intelligent and enterprising Polish man, that clothes made to measure will cost him less and fit him better than an off-the-shelf Ferragamo, but he refused to hear good sense. Perhaps, like many people, he felt helpless in his inability to visualize what he would like for himself. When asked by the master craftsman “Would sir like a double-breasted jacket or a single-breasted one?” most people reply “Oh, I don’t mind” meaning not that they do not care, but that they don’t have a clue what they want. (An apt metaphor for the whole of their life). The store with ready made clothes offers three choices — which has the virtue of being easy to choose from, even if none is especially good; but the tailor offers endless opportunities; which is, despite Hollywood propaganda to the contrary, not what people want. Don’t ask me what I want. I don’t know what I want. I want everything. I want nothing.

Tracking down my old tailor last month, after three years’ absence, I discovered he had moved to the suburbs and his waiting time is now not three days but — three months. This is not a measure of his success but a measure of the profession’s failure: no one else sews anymore; he is the last tailor shop left in town (not counting the fake, tourist “suit and two shirts” shops which do not actually know how to sew, just how to sell). His prices aren’t up, just like the flat prices of silk, but his waiting times are. His customers are old timers who had learned in better times how to have things tailored (i.e. how to visualize what they want and then instruct it) but can’t afford a higher price: they will rather wait three months than pay more. The younger generation have the money, just no clue what they could tailor, or even that they could.

And yardage — yardage will only sell if you can sew it. If you don’t know what to do with it, you’re not going to buy it, are you?

This is how the demise of one profession (tailoring) leads to the demise of another (weaving). But, hey, no loss without compensation: you can buy 80-dollar T-shirts from LuLu now, mostly in shades of grey, in machine-spun spandex.

I went out and bought four meters of every length of shot raw silk I liked, figuring that, at this rate, in two years’ time when I return again, there won’t be any left.

Some thoughts on encountering Bruckner, at last

As a certain Leopold M. once observed to his far more famous son, the frequency of good days decreases parabolically with age, until, at some point — about now, for me — one is no longer ever well; and content just to bless any merely ordinary day.

As ordinary days go, last Saturday sucked a class-C hurricane: the usual boring health nonsense, unfaithful girlfriends, disloyal friends — and others asking to borrow money — was more than augmented by a veritable conjunction of bad juju: ordered goods undelivered, phone calls unanswered (and others interrupted), online bookings rejected, ATM cards eaten by some machine, brokers calling to say previously confirmed orders hadn’t really gone through, emails bouncing and others arriving without the requested assignments, some bureaucrat or another saying I haven’t produced a sufficient number of pink copies of something, an unexpected accountant’s bill for 1500 big ones.

I arrived home exhausted, disgusted, sick in my heart. I poured myself a stiff one and turned on Mezzo and… was hit in the face by something odd, weird, breathtaking, and… mystifying. What on earth…? Pierre Boulez was stone-facedly waving his hands at something… odd… deeply Germanic, and really very good, which was yet not Beethoven; and, though… both too serious to be either Schubert or Brahms, yet, on the other hand, too… manly (in the non-whining sense) (or should I say, polite?) to be Mahler.

I had a pretty good guess: it had to be the one German I had not known.

And it was: Bruckner’s 8th, 4th movement, the last 20 bars or so of it.

Having promptly located a recording by Jochum, I now realize why Mahler, who’d thought Bruckner his most important artistic influence, insisted on correcting Bruckner’s scores: it has a rather weak middle. But the ending is superb: a sharply climbing motif — anyone but a German might call it hysterical — a questioning note, poignant, yet heroic enough to stop just short of panic — repeated — repeated? sliced! — incessantly into the sea of all of the symphony’s major themes suddenly rising about it in the strings like a fast-gathering dusk… into a kind of triumphant… cacophony.

It was very good, indeed.

Bruckner was an odd fellow: a village school teacher’s son made good, he’d never learned to rebel, trust himself, or ignore his bosses (the von’s, it is said by the usually anti-aristocratic bourgeois historians, but really — the Viennese; the bourgeois always find a way to blame us for their own faults). Still in his forties he was commuting from Linz to Vienna to take courses — and certificates (1). And when critics ripped into his work, he rewrote it. (Very admirable, this, if you ask me; one can’t help feeling many composers’ work could have been greatly benefited by half the humility).

Anyhow, what I wanted to say is this:

1) I am thankful for art because without it my life would be nothing but the predictable succession of dull, boring, painful same-old-same-olds.

2) And: who would have ever thought that — at my age — I still had new things still to discover?

*

But I have to proceed advisedly with my new-found project of listening to all of Bruckner’s symphonies: important friends — ones who often pass through my living room at strange hours — and never ask to borrow a penny — are offended by the Germanic symphony thinking it… rude. Badly mannered. And therefore… repulsive.

Let’s not confuse depression and anxiety with depth, they say.

And right they are.

They are not the only ones, either. Simon Pinker — er — Rattle, sorry, what was I thinking? — faced a rebellion by his bosses (the Berliner Philharmoniker is owned by its musicians) for refusing to play the Germanic repertoire. Oh, God, he mumbled to himself, let’s not have this heavy handed… thing, again! No, no, no, said his bosses, let us have this heavy-handed thing, this is who we are.

One has to admire this single-minded commitment to one’s heritage, however — ah — tiresome — it may be.

__

(1) Note: nothing more bourgeois than a certificate, including the certificate of nobility. It has always been thus: if you need one, you aren’t.

Recent Comments