Of air and lies

November 2011

The invisible visible air of New Delhi

How do you know your plane has started descent towards The New Delhi International Airport? When you begin to smell car exhaust inside the plane’s cockpit. Inside the terminal the smell persists and as you step outside, an acrid, sour, burning smoke assails your eyes and nose. On the way to the guest house you keep the taxi windows closed and try to breathe into your hankie to protect yourself from the nauseating effects of the blue cloud through which your taxi is moving.

At the guest-house you are welcomed by the charming, helpful and efficient hostess who yet manages to surprise you with an oddity: “What’s with the air?” you ask her (meaning: “Has something happened? Was there an explosion? A fire downtown?”) and thinking that, surely, the sheer scale of the disaster would have been first page news. But it hasn’t been: the hostess is nonplussed. “The air? Oh, in the winter it always gets foggy here, and then the dust blows in from the desert.” When you tell her that you have spent several winters in Delhi in the past and that the blue color of the air outside, its acrid smell of combustion, and the huge dust particles that palpably bounce off your face are like nothing you have ever seen before, she is surprised.

You then realize that your hostess is somewhat in the old line of pucca (“proper”) ladies and lives in a kind of purdah (“seclusion”), hardly ever going outside; and that remaining all days indoors has protected her in part from the worst of the pollution outside. Plus, the change in the quality of air must have been to some extent gradual, and therefore people living in Delhi without interruption may have been less aware of it. Still, there must be another cognitive mechanism at work here: the difference between Delhi air in November 2011 and November 2006, the time of my last visit, is so stark that no one with any sense can possibly have failed to notice it – unless they do not want to. And the truth is that most Delhites are trapped in the city and have nowhere to flee to; all they can do is pretend that things aren’t really as bad as they are and hope it will pass.

It will not. In the last decade, the city has moved most public transport to greener liquified natural gas and built a metro to try to ease the traffic congestion; yet the rise in motor vehicles has continued unabated, turning Delhi roads into one huge snarling traffic jam; and the construction of a whole new city of Gurgaon, just south of Delhi, though it has sucked out some old Delhites, has done nothing to abate the relentless population growth as more people move in from everywhere to take advantage of Delhi’s higher wages. Delhi air, never especially good, is far worse today than it was ten or even five years ago and for some, like myself, is simply unbearable.

Although statistics are not easy to come by – government’s annual surveys of Delhi air quality have not been published since 2009 (having been suppressed, some say, for the sake of not scaring off the Commonwealth Games in 2010) – reports circulate that two in five Delhites suffer from respiratory ailments. Certainly all of the city’s professional drivers hack and retch; the pollution has performed a public health miracle: unable to breathe, most seem to have quit smoking.

By miracle of evolution, we’re each a little different, and some of us are better equipped to handle the pollution: I find one of my fellow guests at the guesthouse – a North European – is actually sunning himself on the open-air terrace the next morning. Yet, even he’s not blind: yeah, he admits, the air is bad – better taken in through a cigarette filter, he quips – but at least it is better than last time I came through, a week ago. “Now, that really was bad.” I shudder and thank God I was not in Delhi a week ago; but do recall reading Delhi’s weather forecast at that time: “dry, it said, high 30 degrees centigrade, smokey”. Even Yahoo Weather noticed something was up with the air.

Originally, I had booked my Delhi room for two weeks: the plan was to spend part of the season in the city to catch as much classical music and dance as I could – in quickly “modernizing” India her classical performing arts are progressively more difficult to see; but after just three days, during which I did manage to catch one very good vocal concert (well attended but by an audience of whom none – except myself – was less than fifty), I realized I would have to leave Delhi if I wanted to live: I was choking on the air, feeling physically sick. A friend offered his house in the hills and a spare servant. “Go up there, he said, the air is good, the views are astounding, the walks invigorating.” I had missed the hills almost as much as I had missed India’s classical arts, so instead of rescheduling my flight and advancing my departure from India, I headed for the hills. Ten days is a short time for a Himalayan trip – it takes so long to get there – but that seemed a better idea than to leave India defeated, after mere three days, probably never to come back.

Two days later, about seven in the morning my car came into the full view of the Dhauladar Range. It looked, as always, magnificent; but looking down a bit, around the mountains’ midriff, I suddenly spotted clearly against her snow… clouds of brown smoke meandering in the upper air. Smog!

Around noon, the host took me up to see a property he’s contemplating buying (in order to escape Delhi air). He had selected a beautiful site: within easy access from the State Highway, yet screened from her noise by a low, but steep hill, it sits across the top of a mild hillock, with views in all directions: the Himalayas in the back, the plains in front. On a good day, he says, you can see all the way to Chandigarh; I follow his gesture but all I can make out is milky-white haze of sunlight scattered in the fine dust suspended in the air. “A bit of a fog today”, says my friend, though the temperature is in mid 20s, it has not rained in three months and the air is bone dry; “but look at the mountains, aren’t they magnificent?” They are; though a bit hard to see, veiled as they now are by a purplish-brownish haze. Suddenly I remember: The Asian Brown Cloud. I had never seen it before: and here it was, visible from ground level, with the naked eye.

My friend does not notice. “And the air, he says, ah, the air, isn’t it wonderful? That’s why I want to move here!” Actually, the air is not wonderful. It does not have the acrid smell of smoke which it has in Delhi, but it has none of the bracing freshness of mountain air which I remember from previous visits. I now recognize the phenomenon: I have seen it before.

Pattern recognition

I have of course seen it before – in Chiang Mai, Thailand, which, when I first came to live there in 2001, had mostly manageable air, little traffic, and beautiful views of Doi Suthep, a mountain which towers above it. When I arrived there, the city had a small expatriate population; over the next decade agreeable climate, low prices, favorable tax treatment and a good standard of living have caused the expatriate population to rapidly expand. By 2006 major international magazines declared Chiang Mai to be one of the best places to live in the world, throwing expatriate immigration into overdrive. Ironically, the 2006 positive publicity for the city, and what seemed like a quantum jump in new expat arrivals, coincided with the city’s first environmental disaster. Pro-growth policies of the government of Thaksin Sinawatra in part aimed at decongesting the country’s capital, Bangkok, have caused the city’s population to explode from 250,000 in 2000 to more than 2 million in 2011. Policies designed to capture car assembly business have expanded the number of cars on Thai roads even faster. As has been the case with Delhi, infrastructure development did not keep pace. In February 2006 Chiang Mai experienced its first smokey weather.

Both Chiang Mai and North India lie in the subtropical monsoon zone, at the foot of the Himalayas. The monsoon climate means between four and six months of daily rain which washes the air somewhat and six (or more) months of rainless weather, when dust, once kicked up into the air, does not get washed out from the atmosphere and stays airborn indefinitely – until the rains break again. The solid wall of mountains to the north means that the prevailing Southwest winds concentrate air pollution in the foothills – they effectively sweep garbage from the whole plain south of it and dump it overhead.

I first noticed that something was amiss with Chiang Mai air in December 2006, from my motorcycle, on one of my usual trips into the surrounding hills: a stretch of the road which runs along the top of a ridge used to afford wonderful views over successive mountain ranges fading into the distance towards Burms, each bluer and fainter than the one before. But riding along the same road in now I realized suddenly that one simply could not see the mountains: the view had completely disappeared into a kind of milky haze. Unlike my Delhi friend, I realized immediately that the haze was… no mist.

By late January, Doi Suthep – 1600 m mountain at the edge of the city – traffic-willing the top of the mountain is only 20 minutes away – has disappeared from view; by early February, Chiang Mai experienced its first “blue days” – blue clouds of exhaust hanging over its streets, an acrid burning stink of exhaust, palpable dust in the air, brushing one’s face as one rode through the streets.

Traditionally, the tourist season begins in Chiang Mai with the onset of the dry weather, sometime in late October; this is also when most new expatriate immigrants arrive. In 2006, when the first Blue Days arrived, the largest contingent yet has just bought their properties or signed their leases; people were just settling into their furniture when the pollution struck.

Their reaction to the disaster was much like that of my Delhi hostess: they chose not to notice. They had simply invested too much in their move to Thailand to allow themselves to realize that they have made a mistake. With time, the expats began to complain about the air (though usually pretending that there are only a couple bad weeks in the winter). Finally, this year (2012) the penny began to drop (see this discussion) though not before the Thai government began to wonder in public whether it should just evacuate the entire population from the North of the country. And the expats are still blaming it on Thais burning rice-fields in the winter. Yet, the truth is that Thais have been burning rice fields for about 700 years, but the smog reached catastrophic proportions only now — a clear sign that something else is at fault. What? The Asian Brown Cloud emanating out of India and China. Last year there were reports of Chinese pollution causing smog in Western Japan. This year — in Hawaii.

How bad is it? Just look at the photos of Kangra Fort, in Kanga Valley, 550 km north of New Delhi. What you are seeing is not mist. It is the Brown Cloud visible (and smellable) at ground level.

Alarming trends in Asian cousine

The Old Workhorse — Padthai Kung — now increasingly an endangered species:

flat rice-noodles stir fried with shrimp and crushed peanuts

The aesthetisist in me wants to understand just what is going on with Chiang Mai food.

It has never been great — traditionally Chiang Mai-ites have been gourmands (big eaters) rather than gourmets (epicures); but it has always been far better than almost anywhere else in Thailand. Foreign food in Chiang Mai — including Chinese — has always ranged from bad to indifferent — reflecting perhaps the ignorance of the public — you can sell anything to the ignorant in small quantities; but Thai food has always been at least adequate. Yet, in the last two years I have repeatedly had what I have never had here in the preceding eight years: bad Thai food. And what is far, far worse: all my favorite restaurants — all the places I used to eat in daily — are, one by one, going bad.

I really dread the approach of the lunch hour. Where can I go to eat and not be disappointed? I delay the decision and sometimes don’t dare make one at all: skip lunch, eat fruit instead (pomello and mango are still good though prices have risen dramatically), or eat nothing. More often than ever, if I do go out, I find myself poking at the animal feed I am presented instead of the food I ordered, and, unable to force myself to lift it to my lips, leave hungry and with the feeling of being undeservedly persecuted.

And one has begun to experience the heretofore unheard of: the — occasional, so far, and mild, so far, but all the same — food poisoning.

One explanation must clearly lie in the ingredients: there has been a marked decline in the quality and flavor of fruits, vegetables and meat, in a kind of variation of Gresham’s Law: Chinese imports and new hybrid crops developed for crop yields and long shelf-lives rather than flavor and texture are taking over the market (“Americanization”); the recent run up in food prices (between 50% and 100%) has probably only accelerated the process: unable to cope with the price hikes, people (and businesses) are going down the quality ladder.

But this does not explain the sudden prevalence of bad cooking: food that’s overcooked, or under-cooked, or over-spiced, or over-greasy. Sometimes the failures are shocking: how can one explain hard rice in a self-respecting (supposedly) restaurant in a nation of rice-eaters? Perhaps, in an environment of rapidly rising wages, restaurants are having hard time holding on to their kitchen staff and are forced to replace them with the ever-less skilled; but the consumers share large part of the guilt: they fail to drive home the market message that bad food is not acceptable: the quality-wise declining restaurants are as full as they were in their better-cooking days.

How is that possible?

The only explanation I can think of is that the current customers are not the old customers. In a city whose population has grown ten fold in ten years, this is not surprising: 90% of the eaters are people raised on the less-good food common in other parts of Thailand. Indeed, many immigrants are from the country-side where poor ingredients and total absence of fancy foods have been the norm — even in the villages near Mae Rim — a mere 30 minute drive out of town, only low quality ingredients can be had at the market, the farmers habitually selling all their “premium” products into the city. These immigrants are therefore, literally, food-wise speaking, know-nothings.

This no doubt accounts for the proliferation of “fancy restaurants”, with glass, black decor, halogen spot lights, pointy logos — and bad food. Their customers — and they have plenty of them — are not there to enjoy the food: they want to experience the atmosphere, the decor and the service — feel rich, modern, and fashionable — and could not anyhow tell a good dish (from a bad one) if it hit them in the face. It explains the rise in tipping, too: traditionally, one has not tipped in Thailand, as one does not generally throughout the Far East — Asia uses a different economic model for restaurants, one in which the boss pays his workers; but the hommes nouveaux only a few years out of the sticks, have never been served in their lives and, given their low self-esteem, being served makes them feel awkward; the only reason why anyone would ever serve them must surely be — money; and so they tip.

Come to think about it, one can clearly see the same phenomena — poorer ingredients, poorer cooking, less knowledgeable customers, decor-over-flavor, tipping — at work in the restaurant scene of New Delhi.

The raw silks of Thailand

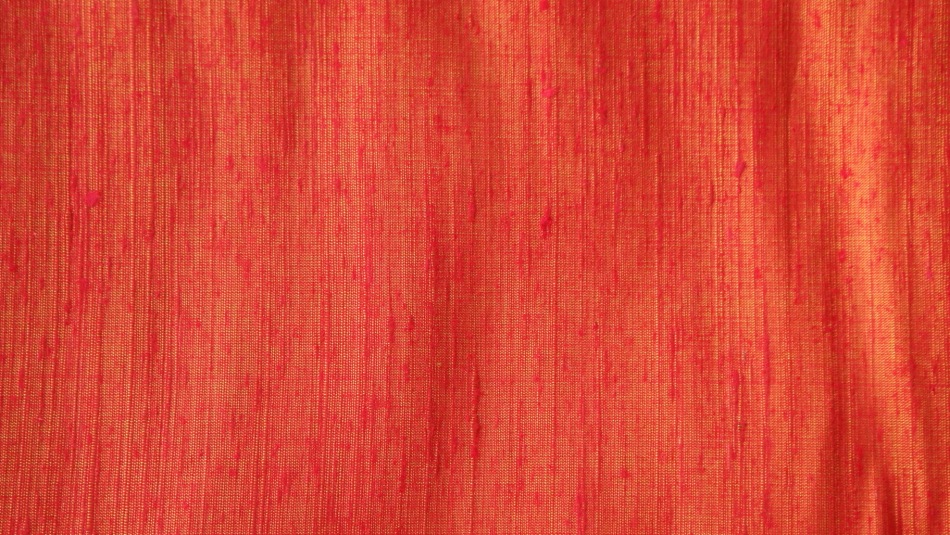

“Raw silk” is silk woven from “the first spin”. Silk cocoons are dumped in boiling water, whereupon the glue holding the string together dissolves and the pot becomes full of mingled, endless thread. One grabs it anywhere and begins to “spin” — rolling it between his fingers while pulling what emerges from one’s hand onto the spinning wheel — trying to get as thin a thread as one can — i.e. one made up of as few fibers as possible. The first spin is invariably a little rough and bumpy, thicker in places and thinner in others as it is knotted, mottled, and various bits of flotsam adhere to it. Later re-spinnings eventually work out the kinks, producing very thin, uniform thread; which is used to weave fine cloth like satin; but the first-spin — in places as thin as the real McCoy, elsewhere as thick as hemp string — can also be used to weave cloth. This is known as Raw Silk. It produces the texture you see above: rough to the touch, uneven, with pronounced individual threads, a bit like the bark of a tree.

Shot silk is silk woven with contrasting warp and weft colors, resulting in a cloth which appears to gleam and shift colors as you turn it before your eyes. These four examples are, top to bottom, red and black, orange and blue, orange and red, and blue and red. Note how they gleam around the fold: this effect — the unique property of shot silk — is especially strong when the cloth is worn as clothing and the wearer moves: she appears to shimmer.

Shot silk is especially effective in satin silk, a type of weave which uses the thinnest, finest thread, and leaves long stretches of individual threads unwoven (“floating” along the surface); this makes the cloth easy to damage, but gives it smooth surface (“smooth as silk”) and brilliant sheen: it seems like the cloth has been woven from pure sunlight reflected on water.

Weaving raw silk as shot silk, on the other hand (as these examples all are) produces a different — and extraordinary — effect: the seamless shifting of colors between the colors of the warp and the color of the weft — the shimmering of light reflected on water — is interrupted by the rough feel created by the the uneven thread. As you bring your face closer to the cloth, the liquid smoothness resolves into dry roughness: it is a lot like a tender kiss suddenly turning into a bite.

The colors of which these four are made up — red, purple, orange — are the basic colors of the Thai language. Purple (Si Muang) and orange (Si Seet) are the two most popular colors in Thailand, seen everywhere: in homes, in clothing, in company colors, on official logos. Not for Thais the dullness of less is more: nature would not allow it; among the intense colors of South East Asia’s nature, “less” really does look like less.

Ten years ago, Kad Luang (“The Old Market”) in Chiang Mai had at least a dozen shops selling silk, both raw and satin, lined along the walls with a fantastic range of colors, starting with white on the left, going through various shades of white (“Monsoon clouds”, “Moon in August”, “Tiger tooth”) to shades of grey to shades of beige to shades of cream, and so on and so on, to umpteen shades of green, umpteen shades of red, umpteen shades of purple, ending, at last, on the far right, at the far end of the store, in several shades of black.

Today only three shops remain and they have, between them, at most 20 meters of linear shelf-space of colored silk; you’d be lucky to find four reds to choose from. The shop owners, there day in and night these twelve years, have not noticed the change, it has been so gradual. But the truth is that silk retail is dying.

Why?

It isn’t the prices: it costs in Thai Baht what it cost ten years ago, a modest 25% climb in dollar terms (between $12 and $18 per meter today). Rather the problem is on the demand side: the government rule that all government employees are required to wear Thai silk on Fridays has been rescinded; marketers have convinced the feeble-minded that denim and spandex are more chic; but, mainly, tailors have gone and closed.

Why do tailors close?

Who knows?

Twenty years ago I tried, in vain, to convince an otherwise intelligent and enterprising Polish man, that clothes made to measure will cost him less and fit him better than an off-the-shelf Ferragamo, but he refused to hear good sense. Perhaps, like many people, he felt helpless in his inability to visualize what he would like for himself. When asked by the master craftsman “Would sir like a double-breasted jacket or a single-breasted one?” most people reply “Oh, I don’t mind” meaning not that they do not care, but that they don’t have a clue what they want. (An apt metaphor for the whole of their life). The store with ready made clothes offers three choices — which has the virtue of being easy to choose from, even if none is especially good; but the tailor offers endless opportunities; which is, despite Hollywood propaganda to the contrary, not what people want. Don’t ask me what I want. I don’t know what I want. I want everything. I want nothing.

Tracking down my old tailor last month, after three years’ absence, I discovered he had moved to the suburbs and his waiting time is now not three days but — three months. This is not a measure of his success but a measure of the profession’s failure: no one else sews anymore; he is the last tailor shop left in town (not counting the fake, tourist “suit and two shirts” shops which do not actually know how to sew, just how to sell). His prices aren’t up, just like the flat prices of silk, but his waiting times are. His customers are old timers who had learned in better times how to have things tailored (i.e. how to visualize what they want and then instruct it) but can’t afford a higher price: they will rather wait three months than pay more. The younger generation have the money, just no clue what they could tailor, or even that they could.

And yardage — yardage will only sell if you can sew it. If you don’t know what to do with it, you’re not going to buy it, are you?

This is how the demise of one profession (tailoring) leads to the demise of another (weaving). But, hey, no loss without compensation: you can buy 80-dollar T-shirts from LuLu now, mostly in shades of grey, in machine-spun spandex.

I went out and bought four meters of every length of shot raw silk I liked, figuring that, at this rate, in two years’ time when I return again, there won’t be any left.

Leaving Chiang Mai

There are many reasons to leave this city: air pollution, horrible traffic, noise (there are no rules about intensity or allowed times for karaoke and Thais have discovered they like it late and loud), fast rising prices, slipping food standards, changing climate, the fact that it has finally made it onto the list of the ten best places in the world to retire to; but for me, the biggest reason to leave Chiang Mai after living here ten years are the “citizens” — the normals, the ordinary, usually elderly, white couples — who come here to settle (and die). For years, one had avoided the expatriate community because it was a little unsavory, a little… perverse: a mixture of missionaries, adventurers, and misfits; the usual stories were of run ins with the law, drunk driving, fights, smuggling, quarreling priests and firebombed churches. Now the dominant element is the lumbering, slow speaking, dull, careful, predictable — and clueless — suburbanite; one flees from them for the opposite reason: nothing remotely kinky ever will come from this crowd. In addition to all the symptoms typical of the worst days of an Asian city’s teenage sickness, another threat hangs over Chiang Mai today: that of becoming Ridgefield Park upon The Ping. The place the old hands had run from in horror, trading it with relief for a bamboo shack, an easy woman, three cases of beer and, on occasion, a tiger, has come after us. It has pursued us long and hard; having arrived, it has laid siege to us with big box retailers, a four lane divided highway, and franchise restaurants. But now it is ready to move on to the next stage: to bind us hand and foot with visa regulations, drivers licenses, proofs of address, fiscal numbers, and medication no longer issued without legal prescription. The habitat of the citizens.

The horror, the horror.

Matmee — Thai Silk Ikats, part 7: Some thoughts on the art and — art in general

In my last post wrote:

“From speaking to and watching the weavers at work one can see that their work is a source of happiness to them: 1) it allows them to experience the satisfaction of flow (concentration upon successful execution of a challenging task); 2) it affords them the aesthetic pleasures of a) looking at beautiful colors and surfaces and b) of bringing things into an order (think of the pleasure of reassembling a picture puzzle); and

3) it is perhaps their only activity in which they can earn cash and admiration for something they do: within the silk world, good weavers are famous; outside of it, in the eyes of the world, they’re just ordinary rice farmers.”

In fact, the relationship of matmee weavers to their work is very much typical of the relationship of all traditional artists to their craft.

Likewise, the experience of the end-user of matmee has all the characteristics typical of the way traditional arts are and have been consumed world over: collectors’ appreciation centers around three factors: a) technical evaluation of the quality of the work and b) of its various technical features, both of which require (and display) non-arbitrary expertise (a piece of silk either is a good work or it is not; the dies either are or are not natural; a weave either is or is not typical of Surin, etc.) and c) a kind of experience of rapture when looking at the dazzling patterns and color combinations.

Traditional arts have worked this way universally – from Patancas to Ibaragi, from weaving to fresco painting: the primary concerns are with technique (its development, acquisition, understanding and command); acquisition and display of a large body of lore; and the experience of rapture in appreciation of the end product.

(By rapture I mean a psychological state induced by the way shapes, patterns and colors interact with our cognitive apparatus on a non-verbal, non-theoretical level. A good work confounds and astonishes the consumer, it literally boggles the mind – makes a powerful but incomprehensible impression, providing a kind of out of the mind experience (“je ne se quoi”): a sense of wonder).

*

Current western theories of art, which have evolved over the last century in response the phenomenon of modern (“conceptual”) art – such as that art is a kind of game (Gadamer), whose rules are negotiated as part of its conduct (Danto), etc. – do not really apply to traditional arts. (Perhaps one could say that they are not specific enough to pick out traditional arts, but it also seems that they are not specific enough to pick out anything: after all, almost any human activity – driving, for instance – consists of negotiating the rules as we go along, etc).

Indeed, traditional arts are best understood in contrast with modern art theory and practice. Main differences lie in two areas, in the area of denotation, and in the area of aesthetic experience.

Denotation

In terms of denotation, discourse in the traditional arts is

1. specific (type of die-used, say)

(Traditional art does not afford the critic the opportunity to display general erudition or verbal playfulness or intellectual originality. A critic either knows something specific, or he is a fool).

2. non-arbitrary (x is or is not in y technique)

(It is expressly not true that an unlimited number of mutually contradictory judgments and opinions concerning a single work are possible: the technique determines unmistakably what is to be judged as good and or bad).

3. never touches on interpretation

(Artist’s “intention” – “meaning” — if any — is given a priori by the genre: Madonnas are for worship, kris are for stabbing, etc. “Traditional arts means nothing”).

Aesthetic Experience

Appreciation of all traditional arts evolves around the work’s ability to spark a mental state which I propose to name rapture – a baffling cognitive response to the work, distinctly non-verbal (“otherwordly”) — indescribable and therefore generally not discussed — but nevertheless essential to any work to be considered of value.

This is not to say that aesthetic rapture is entirely absent from modern art (some pursues it and achieves it) but it does seem that modern art practice is rarely interested in aesthetic rapture; its main interest lies in sparking an altogether different mental state: a kind of intellectual bafflement, i.e. an experience of verbally accessible paradox (e.g. how can there be spiked irons or how can a toilet bowl be an art object, how come 2 + 2 is 4 and not 7, etc.). Traditional arts take no interest in this kind of experience at all.

Indeed, one could say that traditional arts have almost nothing in common with modern art.

Recent Comments