How success kills the goose

How success kills the goose!

Kto słucha nie błądzi was for many months my favorite program on Polish Radio (the last undumbed-down cultural radio on earth). It was also proof that it is possible to talk intelligently about quality in art – in this case, recordings of classical music.

The format was very good: three musicologists with engaging personalities and pleasant voices discussed six different recordings of a single work of music “blind” — i. e. not knowing who the performers were — and choose the best. The program was run on a very high level — this was professionals talking to one another, talking like professionals (“talking shop”) and not minding that someone listening might not know some terms. It’s such a wonderful rarity to hear a program which is not aimed at the 10th grade and below (such programs don’t seem to be produced anymore) — I counted the days between the programs and on occasion cancelled a date in order to hear it.

Unsurprisingly, the speakers’ choices usually coincided with mine. The revelation of the performers at the end of the program also rarely surprised: some performers really are predictably head-and-shoulders above the rest (Gould, Richter, Abbado, Bernstein); but it was pleasant to discover surprising facts, such as that Dudamel actually can conduct (when he’s not conducting a youth orchestra), that Shostakovich played his 2nd Piano Concerto wrong – but better than the score, etc.); and above all it was a lesson in listening: I have been listening to classical music almost “professionally” for forty years now, so it’s no surprise I can hear most of what the musicologists can; but not all – and to learn what they heard and I did not was fascinating.

For an aesthetictist, the program was also a goldmine of observations in the matter of taste: it illustrated that the opinions of those in the business (all participants are musicians and musicologists) are far less divergent than those of the clueless general population (whose preferences being random mean nothing), but that they too face the barrier of personal taste. Yet, at that level of sophistication, the barrier is not a barrier: one cannot help but respects an educated divergent taste.

Like me, the public probably liked to hear what kinds of small details, undetectable to their untrained ears, the musicologists heard in the recordings and why they liked them (or not) — and it grew and grew by the week. But the public liking was the program’s undoing: the organizers – classical radio stations are so happy to have a runaway hit – decided to make it a program with live audience in the studio — and thereby… killed it. The participants began to play to the galleries — unnecessarily showing off their erudition, making pointless jokes and, when they had nothing to say, making things up — lying, to call a spade a spade — as if debates of art and music needed any more lies and fabrication.

(The aestheticist’s lesson here is that taste and perception can be discussed on a very high level but probably not in groups larger than three).

This — the perversion of the author/performer (in this case, the musicologists) is one way in which success kills a good program; the uncalled-for broadening of the audience is another. A Japanese stand-up comedian whose program I once sponsored on Japanese TV told me he stopped enjoying the work the moment his ratings went over 5%. “Suddenly, he said, I discovered that my audience didn’t get my jokes”. His jokes were intelligent and required both wit and lots of erudition to get — the qualified audience size was naturally limited. But as the show became more popular, it began to struggle to reach its new audience, and after some attempts at educating the audience first and then at dumbing-down the content, the host asked us to take him off the air.

Dear Kto słucha nie błądzi : for your own good, today I won’t be tuning in this Sunday.

The raw silks of Thailand

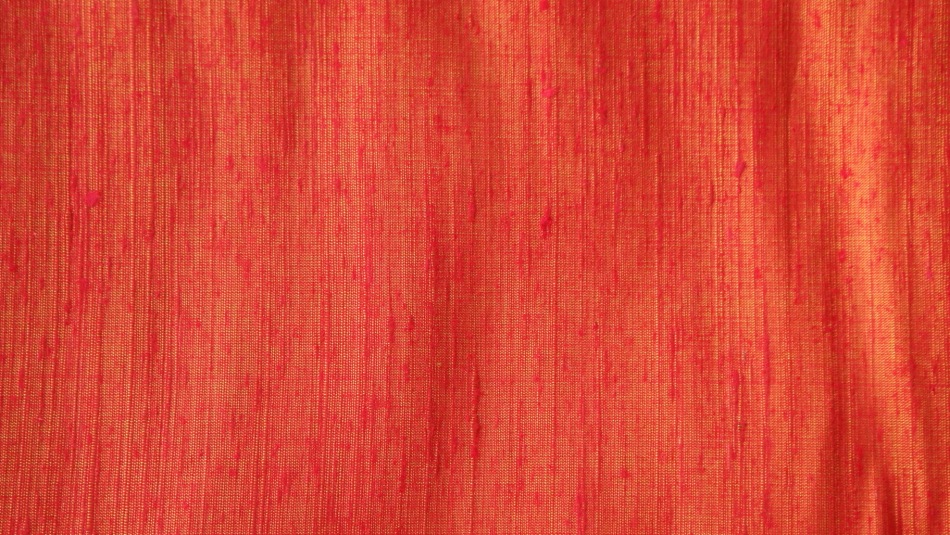

“Raw silk” is silk woven from “the first spin”. Silk cocoons are dumped in boiling water, whereupon the glue holding the string together dissolves and the pot becomes full of mingled, endless thread. One grabs it anywhere and begins to “spin” — rolling it between his fingers while pulling what emerges from one’s hand onto the spinning wheel — trying to get as thin a thread as one can — i.e. one made up of as few fibers as possible. The first spin is invariably a little rough and bumpy, thicker in places and thinner in others as it is knotted, mottled, and various bits of flotsam adhere to it. Later re-spinnings eventually work out the kinks, producing very thin, uniform thread; which is used to weave fine cloth like satin; but the first-spin — in places as thin as the real McCoy, elsewhere as thick as hemp string — can also be used to weave cloth. This is known as Raw Silk. It produces the texture you see above: rough to the touch, uneven, with pronounced individual threads, a bit like the bark of a tree.

Shot silk is silk woven with contrasting warp and weft colors, resulting in a cloth which appears to gleam and shift colors as you turn it before your eyes. These four examples are, top to bottom, red and black, orange and blue, orange and red, and blue and red. Note how they gleam around the fold: this effect — the unique property of shot silk — is especially strong when the cloth is worn as clothing and the wearer moves: she appears to shimmer.

Shot silk is especially effective in satin silk, a type of weave which uses the thinnest, finest thread, and leaves long stretches of individual threads unwoven (“floating” along the surface); this makes the cloth easy to damage, but gives it smooth surface (“smooth as silk”) and brilliant sheen: it seems like the cloth has been woven from pure sunlight reflected on water.

Weaving raw silk as shot silk, on the other hand (as these examples all are) produces a different — and extraordinary — effect: the seamless shifting of colors between the colors of the warp and the color of the weft — the shimmering of light reflected on water — is interrupted by the rough feel created by the the uneven thread. As you bring your face closer to the cloth, the liquid smoothness resolves into dry roughness: it is a lot like a tender kiss suddenly turning into a bite.

The colors of which these four are made up — red, purple, orange — are the basic colors of the Thai language. Purple (Si Muang) and orange (Si Seet) are the two most popular colors in Thailand, seen everywhere: in homes, in clothing, in company colors, on official logos. Not for Thais the dullness of less is more: nature would not allow it; among the intense colors of South East Asia’s nature, “less” really does look like less.

Ten years ago, Kad Luang (“The Old Market”) in Chiang Mai had at least a dozen shops selling silk, both raw and satin, lined along the walls with a fantastic range of colors, starting with white on the left, going through various shades of white (“Monsoon clouds”, “Moon in August”, “Tiger tooth”) to shades of grey to shades of beige to shades of cream, and so on and so on, to umpteen shades of green, umpteen shades of red, umpteen shades of purple, ending, at last, on the far right, at the far end of the store, in several shades of black.

Today only three shops remain and they have, between them, at most 20 meters of linear shelf-space of colored silk; you’d be lucky to find four reds to choose from. The shop owners, there day in and night these twelve years, have not noticed the change, it has been so gradual. But the truth is that silk retail is dying.

Why?

It isn’t the prices: it costs in Thai Baht what it cost ten years ago, a modest 25% climb in dollar terms (between $12 and $18 per meter today). Rather the problem is on the demand side: the government rule that all government employees are required to wear Thai silk on Fridays has been rescinded; marketers have convinced the feeble-minded that denim and spandex are more chic; but, mainly, tailors have gone and closed.

Why do tailors close?

Who knows?

Twenty years ago I tried, in vain, to convince an otherwise intelligent and enterprising Polish man, that clothes made to measure will cost him less and fit him better than an off-the-shelf Ferragamo, but he refused to hear good sense. Perhaps, like many people, he felt helpless in his inability to visualize what he would like for himself. When asked by the master craftsman “Would sir like a double-breasted jacket or a single-breasted one?” most people reply “Oh, I don’t mind” meaning not that they do not care, but that they don’t have a clue what they want. (An apt metaphor for the whole of their life). The store with ready made clothes offers three choices — which has the virtue of being easy to choose from, even if none is especially good; but the tailor offers endless opportunities; which is, despite Hollywood propaganda to the contrary, not what people want. Don’t ask me what I want. I don’t know what I want. I want everything. I want nothing.

Tracking down my old tailor last month, after three years’ absence, I discovered he had moved to the suburbs and his waiting time is now not three days but — three months. This is not a measure of his success but a measure of the profession’s failure: no one else sews anymore; he is the last tailor shop left in town (not counting the fake, tourist “suit and two shirts” shops which do not actually know how to sew, just how to sell). His prices aren’t up, just like the flat prices of silk, but his waiting times are. His customers are old timers who had learned in better times how to have things tailored (i.e. how to visualize what they want and then instruct it) but can’t afford a higher price: they will rather wait three months than pay more. The younger generation have the money, just no clue what they could tailor, or even that they could.

And yardage — yardage will only sell if you can sew it. If you don’t know what to do with it, you’re not going to buy it, are you?

This is how the demise of one profession (tailoring) leads to the demise of another (weaving). But, hey, no loss without compensation: you can buy 80-dollar T-shirts from LuLu now, mostly in shades of grey, in machine-spun spandex.

I went out and bought four meters of every length of shot raw silk I liked, figuring that, at this rate, in two years’ time when I return again, there won’t be any left.

Kinds of minds: chalk and cheese: aesthetic versus contemporary art

(an alternative account of the rise — and place — of contemporary art)

Does contemporary art “make us think”?

Reading Lawrence Weschler’s brilliant Mr Wilson’s Cabinet of Wonders, I am slightly bored. The problem is not the writing – it’s superb – but the topic which turns out to be, as it is, alas, too often the case with Weschler, an item of contemporary art. The writing is superb, but how much can one do with the topic: it is a privately operated museum in LA which liberally and confusingly mixes fact and fiction. Weschler gushes:

The visitor to the Museum of Jurassic Technology continually finds himself shimmering between wondering at (the marvels of nature) and wondering whether (any of this could possibly be true). And it’s that very shimmer, the capacity for such delicious confusion, Wilson sometimes seems to suggest, that may constitute the most wonderful thing about the human being.

Elsewhere Weschler calls this confusion “tension” and suggests it is “aesthetic”.

Anyone trained in experimental science is bound to be underwhelmed: if you study strings, for instance, or prions, you are constantly wondering at (the universe) and whether (the theory put forth to explain it can be true): yet, mostly, it isn’t actually made up. (Hoax in science is to be eradicated, not celebrated). To me, at any rate, the mysteries of science – trying in earnest to learn something about the world we live in – seem a lot more relevant than the contrived conundrums posed by the Jurassic Museum which strike me as fake. More importantly, perhaps, the intellectual tools used to address the mysteries of science are a lot more sophisticated – it actually takes considerable training to as much as follow a scientific argument, a claim which cannot be made about the Jurassic displays.

The simple truth is that, while contemporary art purports to make us think, to me, at least, science does so a lot better.

Aesthetic rapture versus “words, words, words”

Weschler’s book illustrates one interesting feature of contemporary art: that it occasions huge floods of words, words usually a lot more interesting than the art itself. Think of Warhol’s Monroe: no one can possibly claim the work is much to look at, but, boy can we talk about it (reproduction, pop art, suicide, flatness, commodity culture, elitist-pop, color/mood, denial of inner sensation). It’s almost as if the visual insignificance of contemporary art was precisely the element that facilitated talk. A mathematician might write it like this:

P = 1/V

where V = visual power of a work of art

and P = its verbiage-generating potential

The existence of this inverse relationship seems to be confirmed by the existence of arts where high visual appeal goes hand in hand with negligible verbiage-potential. And thus, Bryson, in the introduction to his Looking at the Overlooked, complains about the “lack of variety and complexity of discussion surrounding, for instance, Raphael”. He then goes on to give us 185 pages of complex and varied discussion of Dutch still life. This is perhaps “modern” (“contemporary”?) of him: the art itself did not require such discussion to thrive for three centuries. Huge amounts of it were painted, vast fortunes made (and lost) in dealing in it, middle class homes were filled with it to the brim and – not one essay on the aesthetic tension in buns and cheese! Other such arts – which flowered for centuries without their Brysons – come to mind: tapestries, carpets, tobacco boxes, micro-mosaics, Meissen porcelain.

By contrast, it would be very difficult to imagine any of the material found in our museums of contemporary art to thrive without extensive verbal support.

Perhaps a prominent critic’s comment about one contemporary exhibition can be extended to the whole genre: “very clever, but precious little aesthetic rapture”: where aesthetic rapture supports Dutch still life, for instance, contemporary art seems mostly supported by its power of to generate clever verbiage.

Kinds of minds

I appreciate the controversial nature of the last statement. “How do you define aesthetic rapture”? will be the immediate line of attack. (“How do you define beauty”?) History of European art is littered with the detritus of precisely this debate.

The debate has failed for the same reason for which the great promise of phenomenology has never been fulfilled. Phenomenology arose initially as a kind of epistemological project which proposed to arrive at some convincing understanding of the universe by starting out with precise description of the human experience of it, which was a brilliant idea, except, it turns out, that individual descriptions of experience do not coincide. In a great simplification, what Husserl might describe as his experience of red might strike Brentano as wrong or unfamiliar. The conclusion which seems to have been drawn from this discrepancy is that our conscious states – emotional states – aesthetic states – are vague and illusory and therefore cannot have epistemological value.

It is a false conclusion. My impressions is the only thing I have: if I can’t rely them for relevant epistemological input, I might as well never get out of bed. Rather, the correct conclusion is that, as individuals, we experience qualitatively different conscious responses to the same phenomena. And thus, Weschler seems completely bowled over by the Jurassic Museum while to me it seems little more than a gimmick. Conversely, I expect, that while I am simply astonished by Gerrit’s still lives, Weschler probably finds them indifferent. Yet, that I do, does not invalidate Weschler’s response. Nor vice-versa: that Weschler feels one way does not mean I should (or shouldn’t) feel some other way; or that I might or might not. My experiences are as valid for me as his are to him.

Which would seem to make any discussion of our internal states meaningless – except to the extent that it might broaden our capacity for tolerance – for instance, there are people who actually feel better when they beat their wives; while we should not condone wife-beating we can perhaps as a result of this finding see psychopaths as unfortunate victims of nature and in need of help; except, if it were not for one curious fact: that conscious responses to the same phenomena appear to run in hordes. However you may feel about x – however you may experience color red – chances are that someone – and in a world of 6 billion people probably a very large number of people – experiences the same thing just the way you do, or closely enough for you to recognize it.

This is, of course, predicted by Theory of Evolution. If the human emotional apparatus is a result of evolution, it has arisen as a result of breeding-and-survival competition between different brain models; and, if the human emotional apparatus is still evolving, then, per force, there must exist different emotional brain models within the human population today. In fact, we know that different emotional models exist – introverts/extroverts, for instance – we just refuse to accept the possibility that such different emotional models might produce/experience different aesthetic states in response to art.

Now, we can take this view back to our suggested difference between “contemporary”, that is to say verbiage-generating art, and aesthetic-rapture producing art. For all my respect for Weschler, his powerful intellect, and his superb writing skills (his essay on light in LA was one of he most beautiful pieces of prose I have ever read), when it comes to looking at art, it seems, he and I have different brains. He goes for verbiage, I go for the rapture stuff.

And so you can perhaps guess already what my response to the attack – “How do you define aesthetic rapture”? – would be. And it would be something embarrassingly Zen-like: if you have to ask, you will never know. Verbiage-oriented people probably have no inkling. And if so, then, well, the only way to advance in our discussion of the aesthetic experience is to exclude them as being beyond the pale of the discussion. Not beyond the pale as human beings, of course, but beyond the pale as relevant participants in any discussion of aesthetic rapture. Just the way physicists exclude bankers from technical discussions of black holes.

Art genre as an apartheid tribalism

I suppose that, on this view, an art genre, say a Dutch still life, is a kind of exercise in apartheid tribalism: we aesthetic-rapture still-life-ists produce, show to each other, and trade stuff that (to borrow Jonathan Spence’s brilliant formulation concerning religious people and holy texts) “fits like a key in the lock of our mind”; while they – contemporary talkers – do the same with “contemporary art”. There is probably only limited common ground between the two. This is reflected by many facts; for instance, the usual institutional separation between contemporary art museums and all other museums; or the inability of some ancient languages to assimilate contemporary art into their traditional art terminology (e.g. the Japanese, among whom there are a great number of enthusiastic contemporary art people, are unable to call contemporary art “geijutsu”, which is the word they have invented as a holding category for things like ink paintings, netske carvings, lacquer inlays, and so forth; and feel compelled to call contemporary art… “aato”).

[A small footnote: geijutsu, a term at least 500 years old in Japan, preserves in Japanese the same meaning which the word “art” had in Europe as recently as the 18th century, when we wrote things like “the engineer undermined the walls of the defending city through expert exercise of his art” – it means, essentially, “skill”. “Skill”, not “gab”.]

In short — they do their thing, we do ours. And why not? Should chess players object to anyone playing checkers? God no: for one thing, we don’t want the checkers-players spoiling our game with their ideas of a good game (simple, fast, etc.) You contemporary guys want to do your thing? We’re happy for you. (Checkers players commenting on chess may be just the problem highlighted by Rape of the Masters. Although the title claims the problem is political correctness, it is, in my opinion, mistaken; in fact, the problem described in the book is contemporary-art-style verbalization about aesthetic art).

Falsifying the existence of a discontinuity

In light of this apparent discontinuity between aesthetic and contemporary arts, it is curious that we, in Europe, should insist on producing historical narratives pretending that contemporary art somehow evolved or grew out of everything that has gone before: that there is any kind of connecting thread – never mind logic or compunction – between, say, Raphael and the Jurassic Museum. The appearance of contemporary art should really be seen as an arrival of new men, a rise to prominence of a new mind-type, a new sort of activity; and their successful colonization of state cultural budgets for their use. Of course, it is possible to see how the contemporary art mind needs the reference to Raphael if it is going to appropriate the state art budget: that budget is often created with the idea of promoting some sort of new Raphaels and therefore the contemporary artist has to claim a connection with the same. This has been achieved through various means, including a subversion of the traditional meaning of the term “art” (as mentioned above). But economic expediency is one thing, objective truth another.

Administrative sources of the success of contemporary art

If there really does exist such a dramatic discontinuity between the aesthetic and contemporary arts, how was contemporary art able to arrive at its present prominence? I think one explanation is precisely its ability to generate impressive verbiage. The biggest actual shift in European art of the last 150 years has been the rise of the bureaucratic decision-maker. Until about the middle of the nineteenth century state art budgets, to the extent that they existed, were directed by the rulers themselves – Dukes, Popes, Emperors, Kings, who pretended (some with more success than others) to the role of a connoisseur. “More blue”, said Julius to Michelangelo, and who was there to question him? “Yessir”, replied Michelangelo. (Who was he to question Julius? Translation: the boss’s aesthetic response was sufficient justification for the state’s art budget: no more words were necessary). Today, an artist negotiates with a bureaucrat who may or may not understand what he is doing, but who must, whatever he decides, produce a good paper trail justifying his decision. At this, contemporary art is far better than aesthetic art. It just sounds a lot safer, as well as more impressive, to say that “this exhibit questions our assumptions about blah blah blah and inspires the audience to blah blah blah” than to say “Huysum’s carnations rock and the audience will love them”. Translation: more bureaucrats means more paperwork; which means more verbiage; which means more art that can inspire it. In short, more bureaucracy = more “contemporary art”.

Seven lessons of Evora

1. The topic of the recent discussion being the lamentably declining interest and attendance at classical arts events, I imagined those expressing such views, and living nearby, would jump at the news of both Huelgas and Brabant Ensembles singing only 2 hours’ drive away. Alas, no one had time to make the trip — Saturdays, apparently, are not off for the class in question. For this there are three explanations: a) the respondents wished to avoid me, b) were really too busy to make the trip, or — most likely — c) didn’t care. Here’s your clue, dear friend: the people who occupy themselves professionally with high-brow art, do not actually consume it for their pleasure. Like a girlfriend I once had, they probably relax on Saturday afternoons with Sade and a Mary Huggins Whatshername as if the brain were a muscle, needing to rest after all this Goethe and Josquin.

2. On the bus, four mousy-looking young women behind me and two elderly ladies in front of me talked loudly and incessantly. My partial ignorance of the language protected me from the content, but not from speculation: what on earth could possibly deserve such energetic discussion for two hours straight? It was not Jacob Clement’s motets, I was sure. And I was pretty sure it was not the budget crisis, either. What was it then? The young women may have been discussing nail polish; or (fancy me) sexual techniques. But the old ladies? Their grand-children’s teething problems? Chatting among humans, say Evolutionary Psychologist, is like grooming among monkeys: the content does not matter. I had my proof.

3. To my disappointment, the concert was given in the Cathedral. Cathedrals are cheap places to perform, of course, and the audience may be fooled by the fool’s gold dust of spiritual association rubbing off on anything taking place in a church, but churches, dear friends, are about the worst place to perform and hear music. The sound travels up and then back down where it clashes with the sound made a split second later, the result being a kind of congealed soup of standing hum in which nothing can be heard clearly — nothing, that is, except the labials: mumble mumble XCELSIS mumble PACE mumle S mumble SS mumble SANCTUS (maybe). The best Renaissance choir singing in the focal point of a cross-shaped church sounds like a hot-bed of whithering, snarling snakes.

I thought this had been conclusively proven in Halle in 2004, during a famous Handel concert conducted in a church, at which the RAI reporter swore to me he’d never contract anything sung in a church again (the concert was broadcast by Euroadio). Yet, here we are 6 years on and this stuff still goes on. Why? The only possible reason is that the performers know the audience don’t know. Oh, they’ll like the interior; the atmosphere; the paintings. Who cares if they cannot hear our music?

4. The medieval builders knew that the altar of the cross-shaped church was the worst possible place for acoustics. This did not matter for what happened there: incantations in Latin, which no one, thankfully, understood, sounded only more mysterious when obscured by the congealed acoustic boom; the actual music was intended to take place elsewhere: in the choir, which, being located in the back, over the entrance, and high up — right against the ceiling in fact — delivered a different sort of sound. And better sound it was, I am sure of it: the builders knew what they were doing; and so did the composers and choir singers and choirs conductors. In other words, the pros agreed music-making belonged in the back. So, why can’t modern musicians, if they insist on singing in churches, sing from the choir? The reason, old friend, is that they have come to believe themselves the priests of the modern age: they want to take the center; and, what is worse, the audience expects them to. In the past, the musicians stayed back, producing the music which helped the listeners in front of them achieve the aesthetic rapture which they then confused with whatever they had in front of them, which, in a church, happened to be God. Today, the musicians perform out front: no God, no aesthetic rapture, just a bunch of OK looking middle aged singers whom you simply cannot hear. Come on. You sing beautifully, but, if you want me to enjoy your work, back in the choir with you lot. It was good enough for Bach.

5. Paintings. Wow. The paintings. Don’t get me wrong: I love this country, its people, its food, its… well, everything. But if there is one thing these people cannot do, it is — paint. Would they please stop already?

Alright, let’s be serious: why didn’t they stop while still painting? Did the painters not notice that their work looked like hell? And, more importantly, did not their sponsors? Were the sponsors perhaps the verbal sort, who, when looking at a painting, simply cannot tell that it is crooked and ugly — cannot tell anything, in fact, but its content? (“Jesus? Good. Naked Chicks? Bad”?) A painting is a painting is a painting? It’s a painting, and paintings are art, so, great, here we have a painting, at last, let’s hang it up?

6. Though I have tried to shield my eyes from the sight, I could not: the stuff burnt into the retina of my eye like a branding iron. And while staring at it, I realized that, clearly, expressionism was not invented in 1880’s France and Germany but in 1500’s Portugal: same convoluted gracelessness, same ugly colors, same contorted, tortured expressions. Suddenly, I was struck by the unfairness of it all. Why should Shiele and Munch get all the money and all the praise and all the credit? When a Frenchman does it (or a Norwegian but in Paris, or Berlin), it’s great art, I suppose, but when a Portuguese does it in Portugal, it’s provincial kitsch?

7. At the hotel — cute as per usual, if, as per usual, substandard — at least the mattress was not the usual National Sponge — it turned out that absolutely all rooms look out on the only busy road in Evora — cobble-stoned, too, for added acoustic effect. The guidebook hadn’t mentioned that: it’s writer may not have noticed. The hotel owner disagreed, when I did: oh, it’s very quiet here. I took a double-take. Really? Did she really think so? If so, had she no ears? (I mean it: clearly, paintings in the Cathedral show us that some people have no eyes, so why should not others have no ears, either?) Or did she perhaps have ears but assume that the placebo/hypnotic power of suggestion would take care of the problem: “No, dear sir, it’s not noisy here, it’s all in your mind”. “Oh, it’s all right then.” (?) Is that how’s it’s supposed to work?

And the concert? Other than all the above, it was very beautiful.

Probably. For all I heard. Reminded of how beautiful they were, I rushed back home to listen to my library of Huelgas recordings.

PS. As I waited in front of the Cathedral for the concert to begin, a cold front slowly rumbled in, sending forth across the blue sky the wispy tender tendrils of the first autumn rain. It looked rather good: see above.

What I said at the conference: or: The universal opera mind, the experience of aesthetic rapture, the leading role of the audience, and how economic advancement can kill a perfectly good art

Thai Khon

[Our current art theories are fundamentally flawed. This is important because art theories both inspire artists’ endeavors and determine official arts policy; and false theories of art lead to failure just like false theory of rocket science leads to crashes and false medical theory leads to the patient’s death: art stagnates, artists are frustrated, grant money is misspent, and the public, unserved, loses interest.

That our art theories are false ought to be apparent to anyone with but a modicum of education and experience – a little modern logic, a little modern economics, a little modern psychology, a little travel, a little business experience in the private sector; the trouble is that those who formulate and teach our art theories, and those who attempt to put them into practice, lack precisely that modicum.

It is worse, in fact: our current art theories have evolved a phalange of special interests: professors who teach it, bureaucrats who administer it, several generations of artists who have been raised on it, and a whole tribe of consultants, managers, dealers, and impresarios who live off the economic systems put in place to implement precisely those theories. Any new theory of art which challenges the economic standing of all these people is therefore resisted. And thus, our false theory of art has become a kind of scholastic Aristotelianism, an unassailable dogma, a powerful group-think, and, generally speaking, no genuine debate of it is possible.

At a recent conference I presented an aspect of a dissident point of view. Below is the text of my presentation with marginal annotations in yellow.]

1. Comparing East and West

The idea that one could learn something useful about one’s own culture by comparing it to other cultures is very old in Europe, but it has never been well implemented, mainly because most attempts to do so set out form the assumption that other cultures are so foreign that we could not begin to understand them, let alone find any similarities. Comparisons, when they are made, are focused on differences rather than similarities. Voltaire gave a perfect expression of this view; he wrote: what is in in Peking, in Paris is right out. In other words, all cultural standards are merely conventional, including our own.

In fact, the truth is precisely the opposite: there are lots of similarities and standards are strikingly alike. That Voltaire did not see this is curious: it’s almost certain that as he wrote those words, he had before his eyes somewhere in his office several pieces of Chinese porcelain: it was at the time, very much in both in Peking and in Paris.

And it was only one of many such things which Voltaire – we – should have noticed.

Balinese Gambuh

2. Asian dance-drama

Here is another one: my learned predecessor has just expressed the view, quite common, that European opera is a unique art form in the world. I believe it is not. I believe other ancient civilizations have evolved very similar art forms – similar both aesthetically and socioeconomically – and that it is both possible and useful to compare them and their fates. I propose to do just that today and my topic will be one such art form: Asian dance-drama.

I came in contact with it for the first time in my middle age, having been formed intellectually in the European cultural tradition: I was a great fan of baroque opera already; but, though I had by then spent a lot of time in Asia, I was not at all familiar with Asian theater. My reaction was at first that of wonder at the strangeness of the drama I was watching – the people looked different, they wore flowers in their hair, the musicians sat on the floor and played gongs, the singers ornamented their songs in unfamiliar ways, and I have never seen such dance figures before. But as the play went on, I was struck by a powerful sense of recognition: it was like meeting a masked stranger during the carnival in Venice and suddenly recognizing that the stranger behind the mask is in fact our old and familiar friend. This experience is not unique to me: it has happened repeatedly to cultured Westerners: Walter Spies, Beryl de Zoete, Collin McPhee. It continues to happen every year at the Bali Dance Festival. It happens too frequently to be an accident: it happens frequently because there is really is a very strong similarity there.

I will discuss the similarities next, but first I have to tell you what I mean by Asian dance-drama. I mean by it a dramatic form invented as a temple art in South India sometime around the year 0. It tells classical stories, usually taken from the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, in the form of dance accompanied by an orchestra and a singing narrator, frequently backed by a choir. As Hinduism, and later Buddhism, spread from South India to South East Asia, the dance drama followed, sometimes – oddly – in opposition to the ruling religion (it is almost as if one imported the religion along with its sins). By the 9th century AD, dance drama became an essential part of royal ceremonial throughout South East Asia. The art form has evolved three distinct styles – South Indian, Indonesian, and Thai-Cambodian. All three are still practiced today.

Cambodian lkhaon kbach boran

3. Asian dance-drama and European opera: two branches of the same art?

So, what are the striking similarities between European opera and Asian dance-drama?

I have divided the similarities into three categories.

(1) First, aesthetically speaking, both European opera and Asian dance-drama resort to the same trick for their emotional effect: first, both art forms induce a strong sense of unreality, or otherworldliness, by staging the performances at night, with dim lights, in incomprehensible languages (Venetian dialect in Europe, for instance, or Kawi in Java); by playing music; by singing and dancing rather than acting; by telling well known and often unbelievable stories, frequently in fragmentary form. All these procedures allow the audience to suspend their sense of reality and engage in appreciating the abstract complexities of the performers’ technique: singing or dancing (or both). The complex technique lies at the heart of the art form. It takes years for the performers to master and years for the audience to learn to appreciate. Its appreciation appeals to our visceral, animal nature: we are naturally very sensitive to the sound of the human voice and the movements of the human body. When we are presented with certain aspects of these phenomena, under certain conditions, we can experience rapture. Both art forms seek to induce the experience of rapture through the procedure described.

(2) Although I believe that the central point of both arts is the attainment of aesthetic rapture, there are important similarities between the two art forms as far as their intellectual frame-work is concerned. For instance: the story does not matter in either art form: the stories are told in incomprehensible languages, they are often silly, and they are invariably familiar: there is no sense of suspense of “what happened then?” In both art forms, the libretti are either classical (Greek and Roman gods in opera, Indian epics in dance-drama), or somehow imitate the classics: there is a sense of a loyalty or adherence to the past on the scenario level. Further, on the ideological level, the stories typically concern themselves with the “old virtues” – virtues appropriate to the feudal society: chivalry, courage, loyalty and decorum. Issues of religious observance, ordinary morals, and utilitarian considerations are studiously avoided. The feudal virtues are deemed to be appropriate to, or possessed by, the aristocratic heroes, who are often contrasted with – but not opposed to – the lower classes. The principal concern is with high and low and the contrast is seen as one expressive of quality, or virtue.

(3) Both art forms have played very similar socio-economic function in their respective societies. For instance, both have always been of very narrow social appeal – a minority art form. (Even in the best of times no more than 10% of the population has ever attended opera in France). In both, core users predominate – people who are avid and frequent consumers of the art form and who devote vast amounts of time and money to its consumption, are capable of watching it every night, often the same production several nights in a row, travel long distances to see special performances, and usually sit in the first rows. Both art forms are characterized by repeat consumption: no opera lover would ever say “Oh, I have seen Cosi Fan Tutte already”. Both art forms are very expensive to put on, both in terms of time and money. Both are connected in the popular mind with the national identity: they are thought to be a kind of epitome, or perhaps even, a kind of zenith of their respective cultures. This gives them both the power to legitimize authority: kings and governments have traditionally used them to establish their authority and shore up their prestige. Finally, both art forms stimulate the same kinds of response from non-users: the first, critical, often lampoons the art form because of its unrealistic representation of life (“fat ladies singing”): popular art’s attitude to these art forms is often subversive; the second common attitude of non-users is admiration and aspiration: “I wish I could appreciate it”.

Cambodian lkhaon kbach boran

And now, allow me to engage in a spot of speculation:

4. Is there such a thing as the opera mind?

Are there enough similarities between opera and Asian dance-drama for us to suggest that they represent a single genre – in fact, the same art form with only minor, cosmetic differences? And if so, can we say that the two art forms have arisen in such similar ways because their particular “trick” fits somehow some aspects of the human mind? If so, it certainly does not fit, as audience participation shows, all human minds: it appeals to a minority of minds in each society where it is present, but, significantly such a minority seems to exist in many different societies. It is possible to take Italian opera to Warsaw in the year 1628 and stage it there without any audience training whatsoever and find that the art form appeals to some of these unprepared minds. Similarly, Indian dance drama can be taken to far away places like Laos and Bali and – be liked by some people there. I am reminded of the Parable of the Sower:

At that time, when a very great crowd was gathering together and men from every town were resorting to Jesus, he said in a parable: “The sower went out to sow his seed. And as he sowed, some seed fell by the wayside and was trodden under foot, and the birds of the air ate it up. And other seed fell upon the rock, and as soon as it had sprung up it withered away, because it had no moisture. And other seed fell among thorns, and the thorns sprang up with it and choked it. And other seed fell upon good ground, and sprang up and yielded fruit a hundredfold.” As he said these things he cried out, “He who has ears to hear, let him hear!” (St Luke, 8:4-15)

We know from experience that different people have different personalities; and we know from Evolutionary theory that a limited variety of different cognitive skills can be expected to co-exist in any human population. Ergo, perhaps there is such a thing as an Opera Mind: a mind especially suited to this type of art form? (“The good ground”). If so, then the invention of the art form was not so much an invention as it was a discovery: a discovery of a certain kind of mind. The fact that the rules of the Italian opera genre established themselves within just twenty years and have remained largely stable since seems to support the thesis: this is the nature of all discoveries which suit underlying reality: the general outline of the invention comes into being quickly and once it does, it remains remarkably stable: think of automobiles: within two decades, automobiles already looked a lot like today’s cars because that was the form that suited the human body. Similarly, the rules of Asian dance-drama have remained, as far as we can tell, largely constant over the last thousand years — perhaps because they suit the dance-drama/opera mind?

I cannot resist counter-factual speculation: if the dance-drama mind is in fact the opera-mind, would staging Venetian opera during the dance festival in Bali meet with the same sense of recognition among the Balinese which I experienced upon my first viewing of Balinese dance-drama? We don’t know that, but, luckily, it is not too late to perform that experiment. But the reverse experiment has been performed: the Royal Cambodian Theater performed in Paris in 1906 and the performance was a huge success with the Parisian cultivated classes. (For some reason it was never repeated).

[So here are some unorthodox ideas for you, such as:

a) that there may exist different kids of minds and that different kinds of art may be designed to fit these different kinds of minds;

b) that these arts may therefore not be fungible – i.e. that arts designed for a certain kind of mind will never fit another other kind of mind, and vice versa;

c) that the distinctions between different kinds of minds – and therefore different kinds of art – can cut across different societies and manifest themselves in many different civilizations; and therefore

d) that certain kinds of minds in Europe and in Asia may be more similar to each other than they are to some of their own peers.

These ideas are strongly resisted by the Art Theory Establishment which holds, in direct opposition, that the mind at the time of birth is a blank slate and that any kind of art can be inscribed upon it. (With the necessary corollaries that the task of inscribing upon it should be paid for by the state and entrusted to the guardians of Art Theory who shall then inscribe upon this very blank slate a kind of art which will benefit the whole society, make it happier, richer, more harmonious and more virtuous).

But if true, these ideas would have many far-ranging consequences, one of them being rendering wholly impossible any utilitarian (“greatest good of greatest number”) arguments in favor of public support for opera. This may not necessarily be bad – opera can survive – even thrive – on its own – it did on 17th century Venice, in Warsaw ca. 1800, in Paris between the wars; indeed, it may be good: freed of any further need to broaden its appeal beyond its core users, to educate the broad public and satisfy indifferent bureaucrats, it just might deliver better the one thing that makes it a great art: the experience of aesthetic rapture.

Which, of course, is another unorthodox idea. The established art theory does not recognize the aesthetic experience at all: it is thought to be “just an emotion”, and “socially constructed” (and therefore arbitrary). Establishment art theorists like to credit the importance of opera to its function as civil liturgy (?), its ability to manipulate signs and symbols (??), it’s education value (all those half-baked ideological messages, I suppose, such as “love is most important” and “love your country”), etc. This makes me often wonder whether the people who write this kind of stuff have in fact ever experienced aesthetic rapture, and if they have not, then, what business do they have to tell us what opera is about?]

Javanese Wayang Orang

5. The Fate of Asian dance-drama in Bali and in Thailand: the role of the educated audience

Now I would like to devote a few words to the modern fate of Asian dance-drama as I think it contains some important clues to understanding what makes an art thrive. There is a tremendous difference between Bali, where Asian dance-drama thrives, where nearly everyone is involved in its performance and consumption, and where the artistic level is very high, and Thailand where it is, quite literally, on its last legs and the one National Theater cannot be filled even for four performances a year.

Indeed, one of the saddest experiences during my study of Asian dance-drama was to see a performance of Thai dance-drama (khon) in Bangkok in 2005. It took place at the National Theater, a grand building founded by the state, and was performed by the Royal Thai khon troupe, which is fully supported by the state. The audience consisted of perhaps two thousand high school kids herded in by their school who had no interest in the performance and talked and played with their mobile phones throughout. The performance was absolutely terrible: the orchestra played with all the oomph and gusto of ripe Camembert, and the dancers could not be troubled to lift their legs so that it was impossible to say whether they could dance at all. I thought I’d just seen the death of khon.

And then, only two years later, I saw the same troupe perform in Bali. The difference between the two performances was night and day – and the explanation for the difference seemed… the audience. The audience in Bali is knowledgeable and experienced and it gives ready expression to its likes and dislikes. This leads to a special rapport between the audience and performers and motivates the performers to try harder; and they do. On that night, the Thai khon dancers appeared to be gods come down to earth: they did not move, they floated.

The existence of knowledgeable audience probably explains the excellent condition of dance-drama in Bali where a very large number of amateur troupes (nearly every village has its own theater troupe) performs it throughout the year and where the annual dance festival features several simultaneous performances – to packed audiences – throughout the day for a whole month. The difference in the audience is probably explained by the education: growing up in Bali obliges one to dance and play music since childhood. Dance education begins around the age of 3 and continues till death: nearly every adult participates in some artistic ensemble in some capacity. By contrast, classical dance drama education, which had once been part of any upper-class child’s curriculum, has ceased in Thailand nearly 40 years ago.

[This, by the way, is another view in direct disagreement with the established theory of art. The notion that a knowledgeable audience motivates artists to a better performance, that it spurs them to greater efforts and guides them in their search for new forms of expression runs wholly against the current and general belief that a true artists is someone who leads and teaches his audience, guides it out of its ignorance – indeed, yanks it out of its ignorance and complacency, often against its will, at the cost of tremendous self-sacrifice and professional failure in his lifetime. (i.e. only future generations can appreciate the work of a genius working today who must, by definition, be “ahead of his time” and therefore misunderstood).]

Keralan Kathakali

6. Is Europe going Thailand’s way?

Incidentally, this is what is happening in Europe: the generation of our grandparents was taught to sing and play the piano – and not just at a rudimentary level: a reasonable level of expertise was required — enough to perform Beethoven and Schubert piano sonatas. This level of expertise made it easy for that generation to learn to appreciate opera and assured a steady audience for operatic productions. Today hardly anyone receives any musical education, and if they do, it is at best elementary. Appreciation of classical arts requires cultivation: not hours, but months and years of training the eye and the ear and today we do not devote that kind of time to cultivating ourselves. Is it any surprise that the popularity and commercial viability of European opera is going the way of Thai dance-drama?

7. The economic decline of the upper-middle class the death of art: can we even hope to have great opera for long?

And this is a good moment to ask ourselves a philosophical question: given the way our society has changed in the last century, and in particular the way the life of the middle and upper-middle classes has changed, can we even hope to foster a broad, educated audience for our opera? Only a hundred years ago a doctor, a lawyer, or an engineer would leave for work at 10 and come back home by 3. Within those short five hours he would have earned (and kept) enough income to support a large household with servants. This allowed him and his family not only the financial resources, but also the time necessary to cultivate themselves, to learn how to play the piano and sing, and to amuse themselves by giving amateur ad hoc opera performances at home (such as took place at my grandparents’ house). In today’s middle and upper-middle households, both spouses work and, being professionals, probably work 60- or 70-hour weeks; then they return home to perform household chores themselves. There is no time to become culturally cultivated today. Perhaps we have to accept that opera is an art of a bygone era: an era when we had time for it.

Recent Comments