Carpet, Iranian, XVI c, Museu de Arte Antiga, Lisbon

An amazingly tightly executed work with beautifully drawn animals, fruit trees, and abstract flowers, very well preserved colors; left and right edges missing, some vertical wear through the center. One of the most impressive carpets I have ever seen — and now it can be photographed!

Heracles slaying the centaurs, Flemish Tapestry, XVI c, Brussels, Museu de Arte Antiga, Lisbon

The disturbingly hydrocephalous features of the heroes is perhaps part of the design: this particular tapestry may have been part of a series (labors?) and destined for a higher section of the wall — in which case, viewed at a sharp angle from below, body proportions would look “right”.

The most striking feature of the piece to me are the fruit-and-flower borders, exquisitely drawn, superbly woven and retaining 500 years later incredible freshness of colors. It is one of the main reasons why I keep going back to the museum.

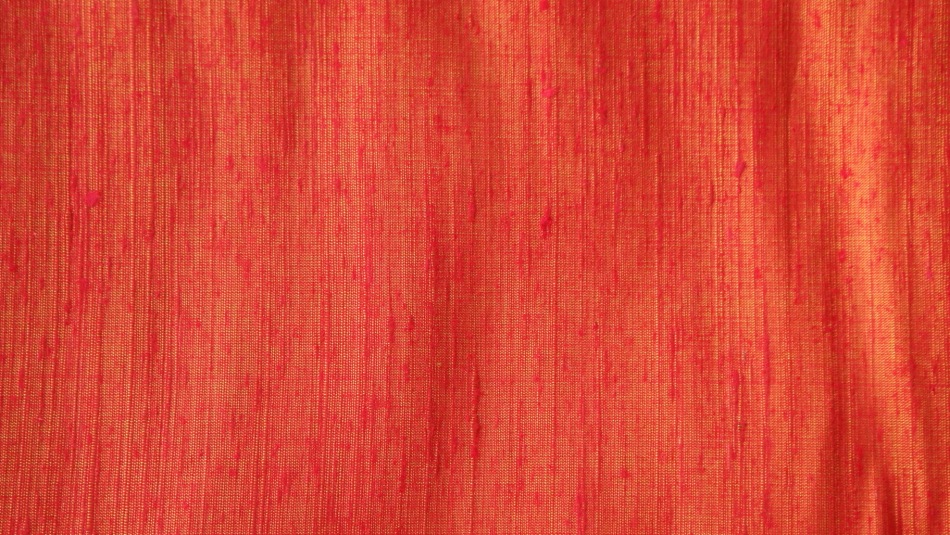

The raw silks of Thailand

“Raw silk” is silk woven from “the first spin”. Silk cocoons are dumped in boiling water, whereupon the glue holding the string together dissolves and the pot becomes full of mingled, endless thread. One grabs it anywhere and begins to “spin” — rolling it between his fingers while pulling what emerges from one’s hand onto the spinning wheel — trying to get as thin a thread as one can — i.e. one made up of as few fibers as possible. The first spin is invariably a little rough and bumpy, thicker in places and thinner in others as it is knotted, mottled, and various bits of flotsam adhere to it. Later re-spinnings eventually work out the kinks, producing very thin, uniform thread; which is used to weave fine cloth like satin; but the first-spin — in places as thin as the real McCoy, elsewhere as thick as hemp string — can also be used to weave cloth. This is known as Raw Silk. It produces the texture you see above: rough to the touch, uneven, with pronounced individual threads, a bit like the bark of a tree.

Shot silk is silk woven with contrasting warp and weft colors, resulting in a cloth which appears to gleam and shift colors as you turn it before your eyes. These four examples are, top to bottom, red and black, orange and blue, orange and red, and blue and red. Note how they gleam around the fold: this effect — the unique property of shot silk — is especially strong when the cloth is worn as clothing and the wearer moves: she appears to shimmer.

Shot silk is especially effective in satin silk, a type of weave which uses the thinnest, finest thread, and leaves long stretches of individual threads unwoven (“floating” along the surface); this makes the cloth easy to damage, but gives it smooth surface (“smooth as silk”) and brilliant sheen: it seems like the cloth has been woven from pure sunlight reflected on water.

Weaving raw silk as shot silk, on the other hand (as these examples all are) produces a different — and extraordinary — effect: the seamless shifting of colors between the colors of the warp and the color of the weft — the shimmering of light reflected on water — is interrupted by the rough feel created by the the uneven thread. As you bring your face closer to the cloth, the liquid smoothness resolves into dry roughness: it is a lot like a tender kiss suddenly turning into a bite.

The colors of which these four are made up — red, purple, orange — are the basic colors of the Thai language. Purple (Si Muang) and orange (Si Seet) are the two most popular colors in Thailand, seen everywhere: in homes, in clothing, in company colors, on official logos. Not for Thais the dullness of less is more: nature would not allow it; among the intense colors of South East Asia’s nature, “less” really does look like less.

Ten years ago, Kad Luang (“The Old Market”) in Chiang Mai had at least a dozen shops selling silk, both raw and satin, lined along the walls with a fantastic range of colors, starting with white on the left, going through various shades of white (“Monsoon clouds”, “Moon in August”, “Tiger tooth”) to shades of grey to shades of beige to shades of cream, and so on and so on, to umpteen shades of green, umpteen shades of red, umpteen shades of purple, ending, at last, on the far right, at the far end of the store, in several shades of black.

Today only three shops remain and they have, between them, at most 20 meters of linear shelf-space of colored silk; you’d be lucky to find four reds to choose from. The shop owners, there day in and night these twelve years, have not noticed the change, it has been so gradual. But the truth is that silk retail is dying.

Why?

It isn’t the prices: it costs in Thai Baht what it cost ten years ago, a modest 25% climb in dollar terms (between $12 and $18 per meter today). Rather the problem is on the demand side: the government rule that all government employees are required to wear Thai silk on Fridays has been rescinded; marketers have convinced the feeble-minded that denim and spandex are more chic; but, mainly, tailors have gone and closed.

Why do tailors close?

Who knows?

Twenty years ago I tried, in vain, to convince an otherwise intelligent and enterprising Polish man, that clothes made to measure will cost him less and fit him better than an off-the-shelf Ferragamo, but he refused to hear good sense. Perhaps, like many people, he felt helpless in his inability to visualize what he would like for himself. When asked by the master craftsman “Would sir like a double-breasted jacket or a single-breasted one?” most people reply “Oh, I don’t mind” meaning not that they do not care, but that they don’t have a clue what they want. (An apt metaphor for the whole of their life). The store with ready made clothes offers three choices — which has the virtue of being easy to choose from, even if none is especially good; but the tailor offers endless opportunities; which is, despite Hollywood propaganda to the contrary, not what people want. Don’t ask me what I want. I don’t know what I want. I want everything. I want nothing.

Tracking down my old tailor last month, after three years’ absence, I discovered he had moved to the suburbs and his waiting time is now not three days but — three months. This is not a measure of his success but a measure of the profession’s failure: no one else sews anymore; he is the last tailor shop left in town (not counting the fake, tourist “suit and two shirts” shops which do not actually know how to sew, just how to sell). His prices aren’t up, just like the flat prices of silk, but his waiting times are. His customers are old timers who had learned in better times how to have things tailored (i.e. how to visualize what they want and then instruct it) but can’t afford a higher price: they will rather wait three months than pay more. The younger generation have the money, just no clue what they could tailor, or even that they could.

And yardage — yardage will only sell if you can sew it. If you don’t know what to do with it, you’re not going to buy it, are you?

This is how the demise of one profession (tailoring) leads to the demise of another (weaving). But, hey, no loss without compensation: you can buy 80-dollar T-shirts from LuLu now, mostly in shades of grey, in machine-spun spandex.

I went out and bought four meters of every length of shot raw silk I liked, figuring that, at this rate, in two years’ time when I return again, there won’t be any left.

Matmee — Thai Silk Ikats, part 7: Some thoughts on the art and — art in general

In my last post wrote:

“From speaking to and watching the weavers at work one can see that their work is a source of happiness to them: 1) it allows them to experience the satisfaction of flow (concentration upon successful execution of a challenging task); 2) it affords them the aesthetic pleasures of a) looking at beautiful colors and surfaces and b) of bringing things into an order (think of the pleasure of reassembling a picture puzzle); and

3) it is perhaps their only activity in which they can earn cash and admiration for something they do: within the silk world, good weavers are famous; outside of it, in the eyes of the world, they’re just ordinary rice farmers.”

In fact, the relationship of matmee weavers to their work is very much typical of the relationship of all traditional artists to their craft.

Likewise, the experience of the end-user of matmee has all the characteristics typical of the way traditional arts are and have been consumed world over: collectors’ appreciation centers around three factors: a) technical evaluation of the quality of the work and b) of its various technical features, both of which require (and display) non-arbitrary expertise (a piece of silk either is a good work or it is not; the dies either are or are not natural; a weave either is or is not typical of Surin, etc.) and c) a kind of experience of rapture when looking at the dazzling patterns and color combinations.

Traditional arts have worked this way universally – from Patancas to Ibaragi, from weaving to fresco painting: the primary concerns are with technique (its development, acquisition, understanding and command); acquisition and display of a large body of lore; and the experience of rapture in appreciation of the end product.

(By rapture I mean a psychological state induced by the way shapes, patterns and colors interact with our cognitive apparatus on a non-verbal, non-theoretical level. A good work confounds and astonishes the consumer, it literally boggles the mind – makes a powerful but incomprehensible impression, providing a kind of out of the mind experience (“je ne se quoi”): a sense of wonder).

*

Current western theories of art, which have evolved over the last century in response the phenomenon of modern (“conceptual”) art – such as that art is a kind of game (Gadamer), whose rules are negotiated as part of its conduct (Danto), etc. – do not really apply to traditional arts. (Perhaps one could say that they are not specific enough to pick out traditional arts, but it also seems that they are not specific enough to pick out anything: after all, almost any human activity – driving, for instance – consists of negotiating the rules as we go along, etc).

Indeed, traditional arts are best understood in contrast with modern art theory and practice. Main differences lie in two areas, in the area of denotation, and in the area of aesthetic experience.

Denotation

In terms of denotation, discourse in the traditional arts is

1. specific (type of die-used, say)

(Traditional art does not afford the critic the opportunity to display general erudition or verbal playfulness or intellectual originality. A critic either knows something specific, or he is a fool).

2. non-arbitrary (x is or is not in y technique)

(It is expressly not true that an unlimited number of mutually contradictory judgments and opinions concerning a single work are possible: the technique determines unmistakably what is to be judged as good and or bad).

3. never touches on interpretation

(Artist’s “intention” – “meaning” — if any — is given a priori by the genre: Madonnas are for worship, kris are for stabbing, etc. “Traditional arts means nothing”).

Aesthetic Experience

Appreciation of all traditional arts evolves around the work’s ability to spark a mental state which I propose to name rapture – a baffling cognitive response to the work, distinctly non-verbal (“otherwordly”) — indescribable and therefore generally not discussed — but nevertheless essential to any work to be considered of value.

This is not to say that aesthetic rapture is entirely absent from modern art (some pursues it and achieves it) but it does seem that modern art practice is rarely interested in aesthetic rapture; its main interest lies in sparking an altogether different mental state: a kind of intellectual bafflement, i.e. an experience of verbally accessible paradox (e.g. how can there be spiked irons or how can a toilet bowl be an art object, how come 2 + 2 is 4 and not 7, etc.). Traditional arts take no interest in this kind of experience at all.

Indeed, one could say that traditional arts have almost nothing in common with modern art.

Matmee — Thai Silk Ikats, part 6: current state of affairs

Matmee weaving has been on an accelerating decline: there are ever fewer weavers as old weavers retire but no young people enter the profession. I know several Khon Kaen girls whose mothers’ weave, and who are proud of their mothers’ work, but who themselves have not woven a thread and would not weave one if their life depended on it: to their minds, weaving stinks of old, passe countryside life which they are eager to leave behind. Almost any other menial city job seems better.

More importantly, mothers choose not to teach their daughters: they prefer for their girls to complete schooling and move to the city. The city seems to them to promise an easier life — even if the girls should end up, as they usually do, in the ranks of city proletariat. And even though teaching their daughters to weave in their spare time, after school or on weekends, would not subtract from the child’s education, but on the contrary, enhance her repertoire of skills, somehow, they do not: weaving does not stand alone in their minds as a valuable skill; but forms an inalienable a part of the village-woman’s life. To their minds, one begins to leave the village by first abandoning the weaving.

Economic incentives play their part, too: it takes between 4 and 12 weeks to weave a full-patterned matmee. This effort is well rewarded for master weavers who turn out the best work, priced in the hundreds-of-dollars-and-up range (remember that the weaving is done in the breaks between other kinds of work!) but in the case of ordinary pieces commanding prices in the under-hundred-dollars range, the financial rewards are not high: a Khon Kaen girl working in a bar in Bangkok makes $30 – $50 a night.

The demand-side economics isn’t good, either: buyers who were reportedly numerous before the Asian Monetary Crisis of 1997, have largely disappeared. Perhaps that crisis had the same effect on Thai middle class that the current global crisis is having on our own middle class today: the middle class itself is coming to an end as we know it. All traditional artists and dealers whom I meet today – world over – tell the same story: the American and European middle class have dropped out form the market completely, leaving only two market segments: cheap junk at the bottom and super-rich at the top. It seems that many of the traditional arts which I am studying will probably not survive the forthcoming two decades of economic stagnation.

The owner of the Chonnabot Thai Silk Factory says his firm used to employ about 100 weavers in late 1980s; on a recent Monday, there were two.

*

From speaking to and watching the weavers at work one can see that their work is a source of happiness to them: 1) it allows them to experience the satisfaction of flow (concentration upon successful execution of a challenging task); 2) it affords them the aesthetic pleasures of a) looking at beautiful colors and surfaces and b) of bringing things into an order (think of the pleasure of reassembling a picture puzzle); and

3) it is perhaps their only activity in which they can earn cash and admiration for something they do: within the silk world, good weavers are famous; outside of it, in the eyes of the world, they’re just ordinary rice farmers.

It does not occur to these women that by failing to teach their daughters, they deprive them of an important source of happiness.

Recent Comments